The Mita System in the Inca Empire and Spanish Colonial Rule

Table of Contents

The Mita system stands as one of the most complex and historically significant labor structures in the pre Columbian Americas, later transforming into a controversial engine of the Spanish colonial economy. Originally developed by the Inca Empire (Tahuantinsuyo), the mit’a system was a form of mandatory public service that served as the backbone of their society. In a civilization that did not use currency, labor was the primary unit of value.

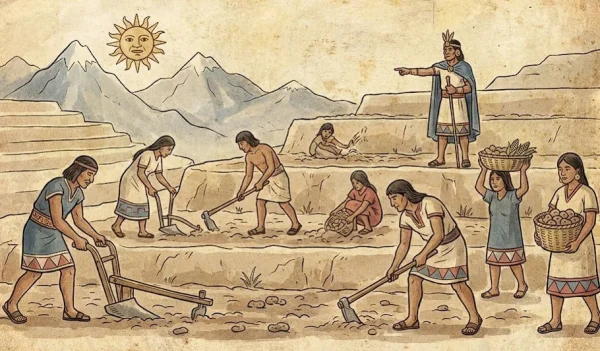

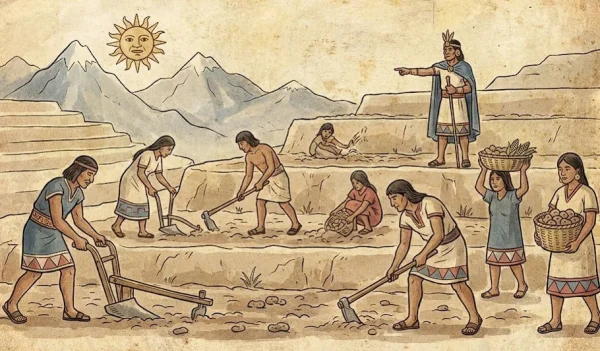

Every able bodied citizen was expected to contribute a portion of their time to the state, building the massive roads, terraces, and temples that still stand today. This collective effort was rooted in Andean reciprocity, ensuring that while the state extracted labor, it also provided security, famine relief, and festivals for the people.

However, the question of what was the mita system changes drastically depending on the era being discussed. Upon the arrival of the Spanish Conquistadors in the 16th century, this indigenous institution was co opted and radically altered. The Spanish administrators, particularly Viceroy Francisco de Toledo, twisted the original concept of communal reciprocity into a system of forced servitude to fuel the mining industry.

The Mita system under colonial rule became synonymous with exploitation, specifically in the deadly silver mines of Potosí, where the principle of “public good” was replaced by the extraction of wealth for a foreign crown, altering the demographic and social landscape of the Andes forever.

To provide a clear mita system definition, one must look at its etymology. The word comes from the Quechua word mit’a, which means “turn” or “season.” In its simplest form, it defined a rotational labor draft. If you were to define mita system in the context of the Incas, it was a mandatory civic duty where citizens took “turns” performing labor for the government.

This was not slavery in the traditional sense, as the workers remained free men and women who were fed, clothed, and celebrated by the state during their service period. It was closer to a tax paid in sweat rather than coin, supporting the welfare of the entire empire.

However, asking what is the mita system in a post conquest context reveals a darker meaning. Under the Spanish, the mita system simple definition shifted from a civic duty to a state-mandated draft for hazardous industries. The “turn” became a sentence. Indigenous communities were legally required to send a quota of male workers to mines or textile mills (obrajes) for set periods, often under brutal conditions with high mortality rates. Thus, the definition bifurcates: it is a story of successful communal cooperation under the Incas, and a tragic mechanism of colonial extraction under the Spanish.

To provide a clear mita system definition, one must look at its etymology. The word comes from the Quechua word mit’a, which means “turn” or “season.” In its simplest form, it defined a rotational labor draft. If you were to define mita system in the context of the Incas, it was a mandatory civic duty where citizens took “turns” performing labor for the government.

This was not slavery in the traditional sense, as the workers remained free men and women who were fed, clothed, and celebrated by the state during their service period. It was closer to a tax paid in sweat rather than coin, supporting the welfare of the entire empire.

However, asking what is the mita system in a post conquest context reveals a darker meaning. Under the Spanish, the mita system simple definition shifted from a civic duty to a state-mandated draft for hazardous industries. The “turn” became a sentence. Indigenous communities were legally required to send a quota of male workers to mines or textile mills (obrajes) for set periods, often under brutal conditions with high mortality rates. Thus, the definition bifurcates: it is a story of successful communal cooperation under the Incas, and a tragic mechanism of colonial extraction under the Spanish.

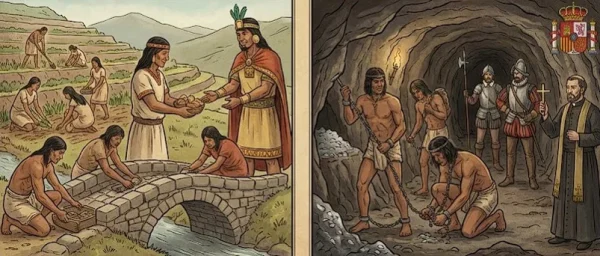

The Inca mita system before Spanish arrival was deeply rooted in the Andean philosophy of Ayni (reciprocity). It was not a one way extraction of value. When asking what was the Inca mita system, it is vital to understand the social contract: the subject provided labor, and in return, the Inca state provided festivals, chicha (corn beer), food, clothing, and security. The work parties were often festive occasions accompanied by music and ritual, turning the drudgery of construction or farming into a communal celebration of the state’s power and benevolence.

The Incan mita system was also rotational and carefully managed to prevent exhaustion. A community would not be asked to send the same men year after year if it jeopardized their own agricultural cycles.

The state kept detailed census records using quipus (knotted strings) to ensure that the burden of the inca mita system before spanish conquest was distributed equitably across the ayllus (kinship groups). This careful management is why the Incas faced relatively few internal rebellions regarding labor; the people perceived the system as fair and beneficial to the collective survival.

The Inca mita system before Spanish arrival was deeply rooted in the Andean philosophy of Ayni (reciprocity). It was not a one way extraction of value. When asking what was the Inca mita system, it is vital to understand the social contract: the subject provided labor, and in return, the Inca state provided festivals, chicha (corn beer), food, clothing, and security. The work parties were often festive occasions accompanied by music and ritual, turning the drudgery of construction or farming into a communal celebration of the state’s power and benevolence.

The Incan mita system was also rotational and carefully managed to prevent exhaustion. A community would not be asked to send the same men year after year if it jeopardized their own agricultural cycles.

The state kept detailed census records using quipus (knotted strings) to ensure that the burden of the inca mita system before spanish conquest was distributed equitably across the ayllus (kinship groups). This careful management is why the Incas faced relatively few internal rebellions regarding labor; the people perceived the system as fair and beneficial to the collective survival.

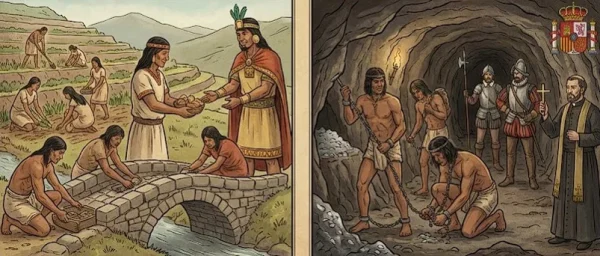

The transition to the Spanish mita system marked a catastrophic turning point for the indigenous population. After the fall of the Inca Empire, the Spanish Viceroy Francisco de Toledo formalized the colonial Mita in the 1570s. He retained the Inca mita system after Spanish conquest in name and structure using the quipu census data to demand quotas but stripped away the reciprocity.

The labor was no longer for the public good; it was for the private profit of the Crown and mining entrepreneurs. The festivals and food provision that characterized the Inca times disappeared, replaced by meager wages that barely covered the cost of food for the worker.

In the context of mita system AP World History, this transformation serves as a prime example of coercive labor. The Spanish justified this exploitation by claiming they were “civilizing” and Christianizing the natives, yet the reality was a demographic collapse.

The Spanish mita system required communities to send one seventh of their adult male population to the mines every year. The conditions were so horrific that communities would often hold funeral services for men leaving for the Mita, assuming they would never return due to accidents, mercury poisoning, or exhaustion.

The transition to the Spanish mita system marked a catastrophic turning point for the indigenous population. After the fall of the Inca Empire, the Spanish Viceroy Francisco de Toledo formalized the colonial Mita in the 1570s. He retained the Inca mita system after Spanish conquest in name and structure using the quipu census data to demand quotas but stripped away the reciprocity.

The labor was no longer for the public good; it was for the private profit of the Crown and mining entrepreneurs. The festivals and food provision that characterized the Inca times disappeared, replaced by meager wages that barely covered the cost of food for the worker.

In the context of mita system AP World History, this transformation serves as a prime example of coercive labor. The Spanish justified this exploitation by claiming they were “civilizing” and Christianizing the natives, yet the reality was a demographic collapse.

The Spanish mita system required communities to send one seventh of their adult male population to the mines every year. The conditions were so horrific that communities would often hold funeral services for men leaving for the Mita, assuming they would never return due to accidents, mercury poisoning, or exhaustion.

Students often ask when was the Inca mita system abolished. Technically, the indigenous reciprocity system collapsed with the fall of the Inca state in the 1530s, but the colonial version persisted much longer. The question of when was the mita system abolished legally refers to the Spanish institution.

It was not officially ended until the Cortes of Cádiz in 1812, and effectively ceased with the independence of Peru and Bolivia in the 1820s. However, forms of coerced labor continued in the Andes under different names well into the 20th century.

The mita system significance extends to the modern day. Economists and historians have traced a long term correlation between areas that were subject to the colonial Mita and current levels of poverty.

The mita system significance lies in its destruction of indigenous social capital and land ownership structures. By repeatedly draining communities of their young men for centuries, the Mita stunted the economic development of the Andean highlands, leaving a legacy of inequality and distrust of the state that persists in the region today.

Students often ask when was the Inca mita system abolished. Technically, the indigenous reciprocity system collapsed with the fall of the Inca state in the 1530s, but the colonial version persisted much longer. The question of when was the mita system abolished legally refers to the Spanish institution.

It was not officially ended until the Cortes of Cádiz in 1812, and effectively ceased with the independence of Peru and Bolivia in the 1820s. However, forms of coerced labor continued in the Andes under different names well into the 20th century.

The mita system significance extends to the modern day. Economists and historians have traced a long term correlation between areas that were subject to the colonial Mita and current levels of poverty.

The mita system significance lies in its destruction of indigenous social capital and land ownership structures. By repeatedly draining communities of their young men for centuries, the Mita stunted the economic development of the Andean highlands, leaving a legacy of inequality and distrust of the state that persists in the region today.

What Was the Mita System Definition and Meaning in History

To provide a clear mita system definition, one must look at its etymology. The word comes from the Quechua word mit’a, which means “turn” or “season.” In its simplest form, it defined a rotational labor draft. If you were to define mita system in the context of the Incas, it was a mandatory civic duty where citizens took “turns” performing labor for the government.

This was not slavery in the traditional sense, as the workers remained free men and women who were fed, clothed, and celebrated by the state during their service period. It was closer to a tax paid in sweat rather than coin, supporting the welfare of the entire empire.

However, asking what is the mita system in a post conquest context reveals a darker meaning. Under the Spanish, the mita system simple definition shifted from a civic duty to a state-mandated draft for hazardous industries. The “turn” became a sentence. Indigenous communities were legally required to send a quota of male workers to mines or textile mills (obrajes) for set periods, often under brutal conditions with high mortality rates. Thus, the definition bifurcates: it is a story of successful communal cooperation under the Incas, and a tragic mechanism of colonial extraction under the Spanish.

To provide a clear mita system definition, one must look at its etymology. The word comes from the Quechua word mit’a, which means “turn” or “season.” In its simplest form, it defined a rotational labor draft. If you were to define mita system in the context of the Incas, it was a mandatory civic duty where citizens took “turns” performing labor for the government.

This was not slavery in the traditional sense, as the workers remained free men and women who were fed, clothed, and celebrated by the state during their service period. It was closer to a tax paid in sweat rather than coin, supporting the welfare of the entire empire.

However, asking what is the mita system in a post conquest context reveals a darker meaning. Under the Spanish, the mita system simple definition shifted from a civic duty to a state-mandated draft for hazardous industries. The “turn” became a sentence. Indigenous communities were legally required to send a quota of male workers to mines or textile mills (obrajes) for set periods, often under brutal conditions with high mortality rates. Thus, the definition bifurcates: it is a story of successful communal cooperation under the Incas, and a tragic mechanism of colonial extraction under the Spanish.

Understanding the Mit’a Labor System as a Form of Taxation

The mit’a labor system functioned as the primary tax mechanism of the Inca economy. The empire did not tax goods or harvest directly from the individual’s personal land; instead, they taxed the individual’s time. This mita labor system required that able bodied men (usually between 15 and 50) work for a specific number of days each year on state lands (lands of the Sun and the Inca). The crops produced on these state lands went into storehouses (qollqas) to feed the army, the priesthood, and the sick or elderly, acting as a social safety net. The mit a system definition also extended to specialized skills. It wasn’t just agricultural labor; artisans, runners (chasquis), and builders all paid their “tax” through their craft. This system allowed the Incas to mobilize massive workforces without a monetary economy. The efficiency of the mit’a labor system was such that the state could guarantee that no one in the empire went hungry, as the surplus generated by this collective tax was redistributed during times of drought or natural disaster, reinforcing the loyalty of the subjects to the Sapa Inca.The Mita System Definition AP World History and Significance

For students studying mita system AP World History, the concept is a crucial example of how labor systems evolved during the Age of Exploration. The mita system definition AP World History curriculums emphasize is its duality: first as an indigenous method of state building and later as a coerced labor system utilized by European mercantilism. It serves as a case study for the “Continuity and Change Over Time” (CCOT) reasoning skill, illustrating how the Spanish maintained the structure of an existing institution but fundamentally changed its purpose and impact. The mita system significance lies in its role in the global economy of the 16th and 17th centuries. The silver extracted from Potosí by mitayos (conscripted laborers) didn’t just enrich Spain; it fueled global trade, causing inflation in Europe and paying for Spanish wars. It even facilitated trade with Ming China, where silver was in high demand. Therefore, the mita system AP World History importance is not just regional to the Andes; it was a primary gear in the engine of the first true global economy, connecting the labor of indigenous Andeans to the markets of Europe and Asia.The Inca Mita System Before Spanish Conquest and Reciprocity

The Inca mita system before Spanish arrival was deeply rooted in the Andean philosophy of Ayni (reciprocity). It was not a one way extraction of value. When asking what was the Inca mita system, it is vital to understand the social contract: the subject provided labor, and in return, the Inca state provided festivals, chicha (corn beer), food, clothing, and security. The work parties were often festive occasions accompanied by music and ritual, turning the drudgery of construction or farming into a communal celebration of the state’s power and benevolence.

The Incan mita system was also rotational and carefully managed to prevent exhaustion. A community would not be asked to send the same men year after year if it jeopardized their own agricultural cycles.

The state kept detailed census records using quipus (knotted strings) to ensure that the burden of the inca mita system before spanish conquest was distributed equitably across the ayllus (kinship groups). This careful management is why the Incas faced relatively few internal rebellions regarding labor; the people perceived the system as fair and beneficial to the collective survival.

The Inca mita system before Spanish arrival was deeply rooted in the Andean philosophy of Ayni (reciprocity). It was not a one way extraction of value. When asking what was the Inca mita system, it is vital to understand the social contract: the subject provided labor, and in return, the Inca state provided festivals, chicha (corn beer), food, clothing, and security. The work parties were often festive occasions accompanied by music and ritual, turning the drudgery of construction or farming into a communal celebration of the state’s power and benevolence.

The Incan mita system was also rotational and carefully managed to prevent exhaustion. A community would not be asked to send the same men year after year if it jeopardized their own agricultural cycles.

The state kept detailed census records using quipus (knotted strings) to ensure that the burden of the inca mita system before spanish conquest was distributed equitably across the ayllus (kinship groups). This careful management is why the Incas faced relatively few internal rebellions regarding labor; the people perceived the system as fair and beneficial to the collective survival.

Why Was the Mita System Important to the Incan Empire Economy

To understand why was the mita system important to the Incan empire, one must look at the geography of the Andes. To control a vertical terrain spanning rainforests, high deserts, and coastlines without money, the state needed a flexible workforce. The mita system Inca administrators utilized allowed them to construct the immense agricultural terraces (andenes) that fed millions. Without this labor, the agricultural surplus necessary to support a standing army and a complex bureaucracy would have been impossible to generate in such a harsh environment. Furthermore, the Inca mita system was the engine of expansion. As the empire conquered new territories, the conquered populations were integrated into the mita. This served a dual purpose: it integrated them economically into the empire and kept them busy, reducing the likelihood of uprising. The infrastructure created by the mita system Inca workforce warehouses, roads, and forts was the physical glue that held Tahuantinsuyo together. Without the Mita, the Inca state would have remained a small regional chiefdom rather than the largest empire in the pre Columbian Americas.Who Used the Mita System to Build the Qhapaq Nan Roads

When asking who used the mita system, the answer is the Sapa Inca and the imperial administration. The most visible legacy of this labor is the Qhapaq Ñan, the Great Inca Road system spanning over 30,000 kilometers (18,000 miles). What was the mita system in the Inca empire if not a massive engineering corps? Tens of thousands of laborers were drafted annually to carve paths into granite cliffs, build suspension bridges over raging rivers, and pave roads through swamps. This was achieved without iron tools or the wheel, relying entirely on the coordinated manpower of the Mita. The Incan mit’a system ensured that these roads were maintained constantly. Local communities along the road were responsible for the upkeep of their specific section as part of their Mita service. This decentralized maintenance meant that the Emperor could move his armies from Cusco to Quito rapidly. The efficiency of the Incan mit’a system was so profound that even after the Spanish conquest, the colonial authorities continued to rely on these roads for centuries, unable to replicate the engineering feats of the laborers who built them.The Spanish Mita System and the Transformation into Forced Labor

The transition to the Spanish mita system marked a catastrophic turning point for the indigenous population. After the fall of the Inca Empire, the Spanish Viceroy Francisco de Toledo formalized the colonial Mita in the 1570s. He retained the Inca mita system after Spanish conquest in name and structure using the quipu census data to demand quotas but stripped away the reciprocity.

The labor was no longer for the public good; it was for the private profit of the Crown and mining entrepreneurs. The festivals and food provision that characterized the Inca times disappeared, replaced by meager wages that barely covered the cost of food for the worker.

In the context of mita system AP World History, this transformation serves as a prime example of coercive labor. The Spanish justified this exploitation by claiming they were “civilizing” and Christianizing the natives, yet the reality was a demographic collapse.

The Spanish mita system required communities to send one seventh of their adult male population to the mines every year. The conditions were so horrific that communities would often hold funeral services for men leaving for the Mita, assuming they would never return due to accidents, mercury poisoning, or exhaustion.

The transition to the Spanish mita system marked a catastrophic turning point for the indigenous population. After the fall of the Inca Empire, the Spanish Viceroy Francisco de Toledo formalized the colonial Mita in the 1570s. He retained the Inca mita system after Spanish conquest in name and structure using the quipu census data to demand quotas but stripped away the reciprocity.

The labor was no longer for the public good; it was for the private profit of the Crown and mining entrepreneurs. The festivals and food provision that characterized the Inca times disappeared, replaced by meager wages that barely covered the cost of food for the worker.

In the context of mita system AP World History, this transformation serves as a prime example of coercive labor. The Spanish justified this exploitation by claiming they were “civilizing” and Christianizing the natives, yet the reality was a demographic collapse.

The Spanish mita system required communities to send one seventh of their adult male population to the mines every year. The conditions were so horrific that communities would often hold funeral services for men leaving for the Mita, assuming they would never return due to accidents, mercury poisoning, or exhaustion.

Differences Between the Inca Mita System and Spanish Mita

Comparing the Inca mita system after Spanish arrival to its pre contact predecessor reveals the stark differences between the Inca mita system and Spanish mita. Under the Incas, the Mita was a seasonal service that respected the agricultural calendar; men were not taken during harvest times. Under the Spanish, the quotas were rigid. If a community had lost population due to disease, the remaining men had to work double shifts to meet the quota, leading to a death spiral of depopulation. What was the mit’a system originally? A symbiotic relationship. What did it become? A parasitic one. Another key difference lies in the destination of the wealth. The mita system significance AP World History analysis often points out that Inca wealth (food, cloth, infrastructure) stayed within the Andes to support the Andean people. The wealth generated by the Spanish Mita (silver and gold) was exported across the ocean to Europe. This extraction impoverished the local region while capitalizing the European economy. The Inca mita system after Spanish rule ceased to be a mechanism of social security and became the primary instrument of indigenous oppression for nearly 300 years.The Role of the Mita System in the Potosi Silver Mines

The Spanish mita system is most infamously associated with the Cerro Rico in Potosí (modern day Bolivia). This mountain of silver consumed the lives of countless indigenous laborers. The mita labor system drafted thousands of men, known as mitayos, who were forced to carry heavy sacks of ore up primitive ladders from deep underground shafts. They worked in week long shifts, sleeping inside the mines, breathing in toxic dust and silica. The use of mercury for refining silver further poisoned the workforce and the surrounding environment. In mita system definition world history terms, Potosí was the industrial center of the colonial world, and the Mita was its fuel. Without the forced low cost labor provided by the Mita, the extraction of silver would not have been profitable enough to sustain the Spanish Empire. The mitayos were paid a pittance, which they usually had to spend immediately on overpriced food sold by the mine owners, trapping them in debt. The Spanish mita system at Potosí remains a harrowing testament to the human cost of the global silver trade.When Was the Inca Mita System Abolished and Its Legacy

Students often ask when was the Inca mita system abolished. Technically, the indigenous reciprocity system collapsed with the fall of the Inca state in the 1530s, but the colonial version persisted much longer. The question of when was the mita system abolished legally refers to the Spanish institution.

It was not officially ended until the Cortes of Cádiz in 1812, and effectively ceased with the independence of Peru and Bolivia in the 1820s. However, forms of coerced labor continued in the Andes under different names well into the 20th century.

The mita system significance extends to the modern day. Economists and historians have traced a long term correlation between areas that were subject to the colonial Mita and current levels of poverty.

The mita system significance lies in its destruction of indigenous social capital and land ownership structures. By repeatedly draining communities of their young men for centuries, the Mita stunted the economic development of the Andean highlands, leaving a legacy of inequality and distrust of the state that persists in the region today.

Students often ask when was the Inca mita system abolished. Technically, the indigenous reciprocity system collapsed with the fall of the Inca state in the 1530s, but the colonial version persisted much longer. The question of when was the mita system abolished legally refers to the Spanish institution.

It was not officially ended until the Cortes of Cádiz in 1812, and effectively ceased with the independence of Peru and Bolivia in the 1820s. However, forms of coerced labor continued in the Andes under different names well into the 20th century.

The mita system significance extends to the modern day. Economists and historians have traced a long term correlation between areas that were subject to the colonial Mita and current levels of poverty.

The mita system significance lies in its destruction of indigenous social capital and land ownership structures. By repeatedly draining communities of their young men for centuries, the Mita stunted the economic development of the Andean highlands, leaving a legacy of inequality and distrust of the state that persists in the region today.